USA Coin Album: America’s Far-East Coinage

Posted on 3/9/2021

The United States/Philippine series of coins included seven denominations. The centavo and half centavo were minted from the same bronze composition used for the domestic one-cent coin. The half centavo appears to have been created from the same planchets as contemporaneous Indian Head cents, while the larger centavo required a custom blank cutting.

|

|

| This 1937-M Centavo reveals the striking weakness that is common to many coins with the Commonwealth reverse. Click images to enlarge |

|

Half centavos were unpopular and were only coined for circulation during 1903–04. Perhaps due to their limited use, Mint State survivors are quite common. NGC has certified 462 examples, the finest being 16 pieces graded MS 66 RD. While not rare, centavo coins are infrequently found with full red color. I was able to cherry-pick one from a small hoard of beautiful pieces dated 1905(P) that broke during the late 1980s.

NGC has certified 19 examples from that date as MS RD, far more than any other early dates of this denomination. The San Francisco Mint centavos of 1908–20 are very seldom found better than MS RB, but the Manila Mint coins can be found almost fully red from 1925 (the first bearing the M mintmark) through 1941, when production was interrupted by Japan’s invasion of the islands. By far, the most common centavo in a fully red state is the “liberation” issue dated 1944-S. However, most are quite poorly struck. This is a common flaw also found in the 1925–41 Manila coins.

|

|

| The 1918-S centavo with Large S is shown in comparison to a 1917-S coin with the normal size mintmark for the period. Click images to enlarge |

|

One rare centavo that may still be selected as a common coin is the 1918-S issue with the Large S mintmark that was intended for the 50 Centavos denomination. This is seldom seen in Mint State, with the finest examples certified by NGC being a pair of coins graded MS 64 BN.

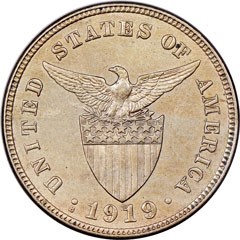

From 1936 onward, all USA/Philippine coins bore a new reverse that proclaimed the islands’ status as a Commonwealth of the United States. This design was the work of Ambrosio Morales, and it replaced the old eagle-atop-shield reverse of 1903–35 coins.

|

|

| Beginning in 1925, Manila Mint coins carried a block M mintmark. The Commonwealth issues of 1936 and later introduced a slender M that was easier to read. Click images to enlarge |

|

The 5 Centavos coins were made from the same planchets used for United States five-cent pieces and were comprised of 75% copper and 25% nickel. This denomination was minted in Philadelphia 1903–08 (1905–08 coins were proofs only), San Francisco 1916–19 and Manila 1920–41 (the 1920–21 issues bore no mintmark). Gems of the 5 Centavos coins are surprisingly rare for all issues prior to the Commonwealth type, although a fair number of 1903(P) and 1904(P) pieces were saved and may be graded just shy of the gem level (MS 65).

When silver coins were reduced in diameter in 1907, a problem arose in that the new 20 Centavos were nearly identical in size to the 5 Centavos. This posed the threat of one being passed, either accidentally or intentionally, for the other. In fact, a rarity was inadvertently created in 1918 when a reverse die for the 20 Centavos was muled with an obverse die for the 5 Centavos. Coined in copper and nickel, the correct value appears on the obverse. However, the risk of the coin being silver-plated and passed at the larger value clearly existed. This is a very scarce variety in all grades, although NGC has two examples graded MS 64 as the finest in its Census.

|

|

| The “mule” 1918-S 5 Centavos variety displays the broad shield and small date of a 20 Centavos die. A normal 5 Centavos reverse is seen on the 1919-S issue. Click images to enlarge |

|

No corrective action was taken at the time because silver coins were hoarded for their bullion value in 1918, but a similar recurrence ten years later forced a change. In 1928, the Manila Mint received an order for 20 Centavos pieces. Since no such coins had been struck since 1921, it was caught without a reverse die dated 1928 and was compelled to press a 5 Centavos die into service.

Though very scarce, this variety is more available in Mint State than the 1918 mule. While its correct value was on the obverse, the incident caused the Manila Mint to address the potential for another recurrence. In 1930, the diameter of the 5 Centavos piece was visibly reduced so that it no longer resembled any other denomination.

When the United States began the liberation of the Philippines in 1944, troops carried with them a new issue of the Commonwealth 5 Centavos coins. These were made in huge numbers at the Philadelphia and San Francisco Mints, the latter continuing production into 1945. Though often weakly struck, gems of these coins are extant. In addition, countless circulated pieces returned with troops and are frequently found among the effects of World War II veterans.

Next month I’ll continue this study of the fascinating USA/Philippines coinage with a look at the silver issues.

David W. Lange's column, “USA Coin Album,” appears monthly in The Numismatist, the official publication of the American Numismatic Association.

Stay Informed

Want news like this delivered to your inbox once a month? Subscribe to the free NGC eNewsletter today!