USA Coin Album: Coin Makeovers

Posted on 10/13/2020

The arrival of a new year is always the time for self-assessment, and this has been true also for the United States Mint regarding its coins. Whether performed for artistic or technical reasons, many US coin types have been revised or touched up from time to time. Therein lies the theme of this month's column.

During the US Mint's first couple of decades new portraits of Liberty and new eagle figures came and went with some frequency, and this was partly the result of trial and error. Some designs proved to be a bit trite, while others simply did not allow the coins to survive the rigors of wide circulation.

Once things settled down a bit, let's say the 1820s, entirely new designs appeared less often. Instead, the Mint's engravers focused on tweaking the existing dies. A big impetus for this was the conversion from open collars to closed collars, which provided our coins with boldly raised rims and uniform diameters.

Perhaps the best example of such revisions may be seen on the quarter dollar. This denomination underwent a brief suspension after 1828, and when production resumed in 1831 the coin looked quite different while retaining essentially the same design elements.

Thereafter, Liberty was trimmer of face and neck and a bit younger, it would appear. The eagle also emerged somewhat more slender, losing its overhead banner in the process. This conversion was less radical for the other denominations, but all were clearly different interpretations of the same devices. It was the cent's bust of Liberty that saw the greatest number of makeovers, with several versions debuting from 1835 through 1843.

|

|

| In 1835 the plump Matron Head Cent (left) was replaced with the more slender Young Head. Click images to enlarge. |

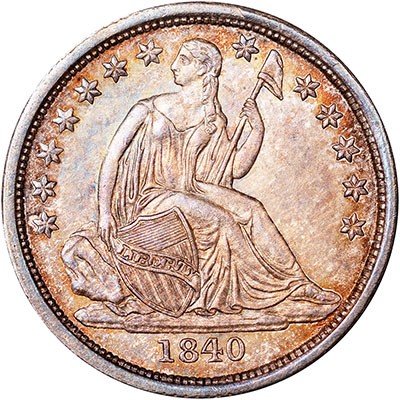

When Christian Gobrecht's Seated Liberty dime and half dime were first coined in 1837, Miss Liberty's posture was a bit strained. Three years later the US Mint called upon artist Robert Ball Hughes to act as chiropractor. He had her sit upright and better fill the field of the obverse, but it appears that he also prepared a feast to celebrate the occasion, as she clearly acquired some added girth. Whether or not that was intended, it certainly is more reflective of art from the period.

During the 19th Century, such revisions were common enough on United States coins that we accept them as a normal practice for the time. In the 20th Century, however, the Mint made a conscious effort to keep any such changes too subtle for non-numismatists to notice. Its efforts were thwarted a bit when outside sculptors were commissioned to provide coin designs.

The result were two very obvious reverse subtypes for the 1913 nickel and radically revised versions of the 1917 quarter dollar. Once the bugs were worked out of these designs, no further alterations were made beyond recessing the quarter's date to protect it from wear in 1925. The nickel would have benefitted from a similar change, but this was never effected, and the result was millions of dateless Buffalo nickels.

The lengthy duration of many 20th Century coin designs led to another form of makeover. The master hub for the Lincoln cent's obverse had been strengthened for 1916's coinage with a degree of hair detail superior to that on the 1909 original. Thereafter, however, this hub was allowed to deteriorate for the next 50+ years. The creation of new master dies annually from this master hub caused it to wear noticeably starting in the 1920s, and the erosion process accelerated with the high mintages of 1934 and subsequent years.

By the time it was used to sink 1968's master die, this hub had worn to the point where Lincoln's portrait had no definable hair strands, and the peripheral mottoes had migrated toward the coin's rim. For the following year, an entirely new obverse master hub was created from Victor D. Brenner's original models. While not as detailed as on the early Lincoln cents, it was a vast improvement over recent issues.

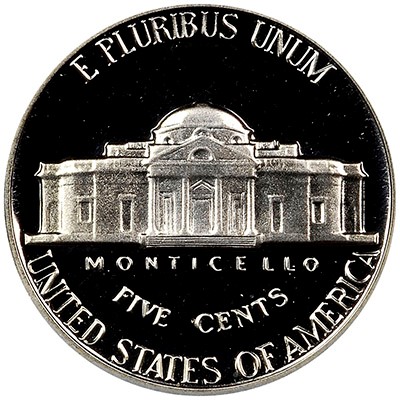

In a similar scenario, the Jefferson nickel of 1938 was coined in huge numbers during its first 30 years, gradually losing its sharp features along the way. New obverse and reverse master hubs were created for the 1971 edition, and these changes are easily seen in side-by-side comparisons with nickels from the previous several years. For collectors seeking Jefferson nickels having the desirable Full Steps detail on Monticello, this was a welcome move.

During the past 50 years or so, the US Mint has made evermore frequent touch-ups to the nation's coins. Some of these have been to address erosion or outward stretching of the master hubs, but another element has been added, too. One requirement of modern, ultra-high speed coin presses is that our coins be quite shallow in relief for mass production.

The concave fields and bold sculpting of earlier issues have been sacrificed to this mandate, though there also has been a great reduction in die erosion and a vast increase in fully struck pieces. While perhaps less satisfying as art, our current coinage has been considerably improved from a purely technical standpoint. This trend is just the latest one in a long history of coin makeovers.

David W. Lange's column, “USA Coin Album,” appears monthly in The Numismatist, the official publication of the American Numismatic Association.

Stay Informed

Want news like this delivered to your inbox once a month? Subscribe to the free NGC eNewsletter today!