NGC Ancients: Incuse Coinage of South Italy

Posted on 6/9/2020

Perhaps the most unusual coins of the ancient Greek world were the ‘incuse’ types struck late in the 6th Century B.C. at a group of mints in south Italy. As Greek colonies, these mint-cities shared a common identity, and were oases within a territory otherwise dominated by the indigenous peoples of south Italy.

|

|

| Bruttium, Caulonia. Stater, late 6th Century B.C. | |

All of these ‘incuse’ coins were made of silver and shared an unusual method of production: broad, thin planchets impressed with a pair of dies that created a design in relief on the obverse and an incuse design on the reverse.

To achieve this impressive, mirrorlike effect, the coins were struck with dies that were leveled and perfectly aligned; otherwise, the dies and the planchets would have been damaged in the process.

Typically, but not always, the principal design was the same on the obverse and the reverse. And more often than not, the fine details, inscriptions, subsidiary designs and border patterns were differently represented on the two sides.

|

|

Shown above are two early Greek staters for comparison. The first, showing a sea-turtle, is from the island of Aegina, not far from Athens. Issued c.550-525 B.C., it is a typical coin of the era, struck on a narrow, thick planchet with no artistic design on the reverse – just the impression of a utilitarian punch. Next is an ‘incuse’ issue of Metapontum in south Italy, dated to c.540-510 B.C. Its diameter, thickness and method of production are quite different from a typical coin of the era.

The ‘incuse’ types of south Italy began about a century after coinage had originated in Ionia, in faraway Asia Minor, yet only about 10 or 20 years after it was first produced at mints in Greece.

Though most of these south Italian cities had stopped making incuse coins by about 500 B.C., Metapontum, Croton and Caulonia continued to do so until c.440 or 425 B.C. Those later incuse pieces were struck on narrow, thick planchets, which meant the incuse reverse was more of a nostalgic feature than a technical achievement.

|

|

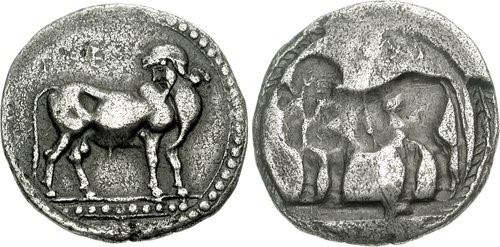

The first mint to strike coins in south Italy may have been wealthy Sybaris, in the region of Lucania, which chose a standing bull as its principal design. Two examples of its early staters, dated c.550-510 B.C., appear above. Sybaris had a rocky history, being destroyed for the first time in 510 B.C. and then being refounded four times, issuing coins each time.

|

|

|

Also from early phases of Sybarite coinage are the three fractional pieces above. First is a triobol showing an incuse amphora on its reverse, next is an obol with an incuse acorn on its reverse, and the last is a hemiobol, weighing merely 0.18 grams, which has an incuse bull on its reverse.

|

An adjunct to the coinage of Sybaris was produced at Laus, originally a colony of Sybaris. However, with the destruction of Sybaris in 510 B.C., many refugees from that city fled to Laus, and in a very real sense converted Laus into a ‘re-foundation’ of Sybaris. Laus chose a most interesting design for its incuse coinage: a man-headed bull. The very rare Laus stater shown above is believed to have been struck c.510-500 B.C.

|

|

Roughly contemporary with the first issues of Sybaris were those of Metapontum, Croton and Poseidonia. Metapontum, another city of Lucania, chose an ear of barley as its principal design. Typically, its earliest coins are dated c.540-510 B.C. Two examples from this initial period – both of different engraving styles – are shown above.

|

|

The two Metapontum staters pictured above are from a later period, c.470-440 B.C. Note how the planchets are narrower and thicker than the earlier pieces. The first of these is still reasonably thin, but the second is struck on a dumpy planchet.

|

|

Also from this later period of ‘incuse’ coinage at Metapontum are the two fractional pieces above. First is a triobol featuring an incuse ox head on the reverse; next is a diobol with an incuse barley grain on its reverse – a perfect companion to the barley ear on its obverse.

Interestingly, the ‘mastermind’ behind the south Italian incuse coinage may have been the philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras, who was no stranger to metal working and whose father had been a gem-cutter, a skill closely related to die engraving.

His proposed role in this coinage, however, relies on an imperfect chronology. Pythagoras migrated to South Italy in about 530 B.C., and many scholars place the first South Italian issues in 550 or 540 B.C. However, even if the timeline hurdle could be cleared, there is no direct evidence linking Pythagoras to the coinage. So, for the moment, the issue must remain just a tantalizing prospect.

|

|

Another early issuer was Poseidonia, a city in Lucania, which created the two incuse coins above, both dated to c.530-500 B.C. They depict the city’s namesake-god Poseidon, who strides forth, raising a trident. The second example is quite interesting as it shows a youthful version of Poseidon on the obverse and an older, bearded version on the reverse.

|

Above is a half-stater/drachm of Sybaris from the same period, but of a crude style.

|

We’ll round out Poseidonia with a double-relief stater of c.445-420 B.C., produced long after the city’s initial destruction and re-founding (indeed, long after it had stopped issuing incuse coinage). Here Poseidon is paired with a bull, which (like the dolphin) was a symbol of the god. It is of exceptionally fine style.

|

|

Another massive incuse coinage of south Italy was produced at Croton, a city in the neighboring region of Bruttium. The people of this city chose the tripod of the god Apollo as its principal design. Above are two staters of Croton, each of slightly differing style, yet both from the early phase of the city’s coinage, c.530-500 B.C.

|

Shown above is a stater of Croton from a slightly later period, c.500-480 B.C. Its planchet is thicker and narrower, and its reverse type is different – an eagle in flight.

|

The next incuse coinage at Croton, c.480-430 B.C., used a narrow and dumpy planchet and dies of relatively crude style. Above is an example of this coinage, a stater which retains the traditional design and adds a standing heron to the left of the tripod.

|

We’ll round out Croton with the rare and intriguing stater above, which researchers believe was issued in alliance with another city in Bruttium, Temesa. Struck c.500-480 B.C., its obverse bears the familiar tripod and ethnic of Croton and its reverse (uninscribed) features a crested Corinthian helmet.

|

Another important issuer of incuse coinage in south Italy was Caulonia, in Bruttium, which chose as its principal design the god Apollo holding a branch and a daimon as he advances toward a stag. An example of the earliest production, dated to the late 6th Century B.C., is shown above.

|

|

Of a markedly inferior style are the two incuse coins of Caulonia shown above. Both are of the early 5th Century B.C., the first being a stater and the second a one-third stater.

|

|

The most prolific issuer of Greek coinage in south Italy was Taras (Tarentum) in Calabria, which is quite interesting since it also was among the last of the major mints in the region to strike coins. The two staters above, likely issued c.510-500 B.C., show a dolphin-rider over a scallop shell.

The boy-on-dolphin motif would be used on the silver coins of Taras until the late 3rd Century B.C. The identity of the dolphin-rider is uncertain, yet scholars agree it is either Taras, a son of the god Poseidon who upon being shipwrecked was rescued by a dolphin, or Phalanthus, the legendary founder of Taras.

Beyond what’s illustrated here, there are some very rare and mysterious incuse coinages, including ones inscribed AMI and SO which do not correspond to any known settlements. A type inscribed ΠAΛ / MOΛ (or just ΠAΛ) may have been issued at Palinourus and Molpa. Finally, one inscribed ΣIPINOΣ / ΠYΞOEΣ may have been issued for Siris and Pyxous, though these settlements were quite distant, making that attribution questionable.

Furthermore, there are some remarkable types which apparently reflect alliances between Croton and Pandosia, and with a re-founded Sybaris. If these coins reveal anything, it’s that much remains to be discovered about the earliest Greek coins of south Italy.

Images courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group, LLC.

Interested in reading more articles on Ancient coins? Click here

Stay Informed

Want news like this delivered to your inbox once a month? Subscribe to the free NGC eNewsletter today!