Chinese Coins: Who Was Norman Bethune?

Posted on 3/10/2020

“My path is set on a strange road, but as long as I feel it is a good road I will go down it,” wrote Dr. Norman Bethune in September of 19371. By then he had twice left his native Canada for wars. The first time was to serve as a stretcher bearer in Europe during World War I. The second call came in the 1936.

Hostility between left-wing Republican and right-wing Nationalist factions in Spain had erupted into a Civil War. Nazi Germany and fascist Italy backed the Nationalists. The Canadian professor of medicine’s plan was find some way, any way he could, to fight the fascists. In Spain, Dr. Bethune spent time at the front. He observed conditions and then devised the mobile blood transfusion service. This team treated the wounded right on the battlefield before the shooting stopped. It was a military medical breakthrough that saved many lives. The Allies adopted it during World War II.

Brilliant, impetuous and irascible, the doctor had to leave Spain in 1937. Back in Canada, he raised money for the Spanish Republican cause. Ever restless and with backing from the Canadian Communist Party, which he joined, Bethune set off in 1938 for China.

The Chinese were hard-pressed by Japan’s invasion. Dr. Bethune arrived in Hong Kong, China together with a Canadian nurse, Jean Ewen. The two flew to Wuhan, where they were introduced to Zhou Enlai, China’s future premier. From there they departed for Yan’an to link up with the Chinese 8th Route Army led by Mao Zedong. Bethune actually met Mao. It was in a cave and the two talked the night away.

While the doctor was not an easy man to work alongside, his knowledge, creativity and dedication were exceptional. A colleague claimed he could, “...finish an operation in calm amid gunfire.”2 Nurse Ewen transferred to another post after four months, but later acknowledged that Dr. Bethune was gentle with the injured and, “No man ever removed so much lead from peoples’ bones, flesh and guts as he did, or set more broken bones...”

Dr. Bethune’s Chinese hosts focused on his selfless dedication to the people. For example, his July 1, 1939 medical report notes, “Our casualties were 280. Our unit was situated (2.3 miles) from the firing line and operated on 115 cases in 69 hours’ continuous work.”3

To teach his colleagues, the doctor wrote medical manuals that were translated into Chinese. So many physicians benefitted from his knowledge and exacting standards that he has been called the “Father of China’s Health Service.”

On one occasion, Dr. Bethune supervised the construction of a hospital. The Japanese bombed it just two weeks after it opened. Neither that nor physical hardship daunted him. “Last month alone, we travelled (400 miles) in the mountains... We walk most of the way, although we have horses. Walking is faster. It is very hard on our feet as we wear nothing but cotton slippers. They only last a few days... We average 25 miles a day.”4

Another time he penned, “The kerosene lamp overhead makes a steady buzzing sound like an incandescent hive of bees. Mud walls. Mud floor. Mud bed. White paper windows. Smell of blood and chloroform. Cold. Three o'clock in the morning, December 1, North China, near Lin Chu, with the 8th Route Army.”5

It was in working conditions like these that Dr. Bethune accidentally cut his finger with a scalpel. The cut became infected. Amputation of his finger would have saved his life, but he refused. Surrounded by Chinese friends, he died on November 12, 1939. His final scrawled message included, “The last two years have been the most significant, the most meaningful years of my life.”6

The West paid little attention to Dr. Bethune’s passing, but China noticed. Mao Zedong himself wrote a eulogy “In Memory of Norman Bethune,” that included, “Comrade Bethune's spirit, his utter devotion to others without any thought of self, was shown in his boundless sense of responsibility in his work and his boundless warm-heartedness toward all comrades and the people. Every Communist must learn from him... A man's ability may be great or small, but if he has this spirit, he is already noble-minded and pure, a man of moral integrity and above vulgar interests, a man who is of value to the people.”

China continues to recognize him to this day. Among other reminders is the Norman Bethune University of Medical Sciences in Changchun city, Jilin province. Dozens of other hospitals and clinics are named after him, too. Since its creation in 1991, the Norman Bethune Award has been “the highest medical honor in China, recognizing an individual’s outstanding contribution, heroic spirit and great humanitarianism in the medical field.”

|

| From top to bottom: The 1998 China Silver 10 Yuan that honors Dr. Norman Bethune, boxed two coin set with Canada's coin and the certificates of authenticity for both coins.

|

It was only in the 1970s that Canada realized that a hero of China was one of its own. After Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s China visit in 1973, Dr. Bethune’s birthplace in Gravenhurst was declared a National Historic Site of Canada. The Government of Canada purchased the home and turned it into a public museum. Numerous other honors followed. One of these was a 1990 two-postage-stamp set for the centenary of the doctor’s birth. It featured matching designs from both Canada and China.

1998 was the 60th anniversary year of Dr. Bethune’s arrival in China. For the first time ever, China released a legal tender coin in cooperation with another country: Canada. Eighty-thousand sets were minted. Each contains a Canadian coin and a Chinese 10 Yuan silver coin. This features a portrait of Dr. Bethune with the words, “THE 60TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE ARRIVAL OF DR. NORMAN BETHUNE IN CHINA,” arrayed in a semicircle above his image.

The coin was struck at the Shenzhen Guobao Mint and contains 1 oz. of .999 silver and is 40 mm in diameter. The design, by Bai Limei, was nominated for the “Best Contemporary Event Commemorative Coin” in the 2000 Coin of the Year award competition.

The involvement of foreign doctors in China’s war against fascism did not end with Dr. Bethune. In 1939, the same year that China lost its Canadian friend, Dr. Jacob Rosenfeld arrived in Shanghai. Freed from a Nazi concentration camp in Austria thanks to Chinese diplomat Ho Fengshan, Dr. Rosenfeld opened what became a successful medical practice in Shanghai. In 1941, as the Japanese rounded up Shanghai’s Jews, he fled the city and volunteered his skills to the New Fourth Army under Mao Zedong’s leadership. “Here in Jiangsu, we are the fortress against fascism and the east most barricade for the freedom of the world. After experiencing the terrible things by the Nazis, I am really pleased to stay with you to fight,” Dr. Rosenfeld wrote.

He found medical conditions at the front much like those that Dr. Bethune struggled with, “The mobile field hospital has to move south. The vast majority of the wounded are on stretchers and only the seriously wounded take trucks. In order to avoid air strikes, the wounded could only be moved at night. Any wounded who could possibly return to combat within a month has to be treated near the front line, as the war was pushing south. Bandage change, emergency surgery and injection of tetanus serum to every wounded.”

Dr. Rosenfeld used simple instruments to save lives. He sometimes was in surgery for 10 hours straight followed by being on call for 24 hours a day. He provided emergency care to local farmers. He delivered numerous babies. His toil and dedication brought widespread recognition and praise. In time, Doctor Rosenfeld became the only foreign doctor to earn senior rank in the army and special membership in the Communist Party of China.

Even the end of World War II did not bring peace for him. In 1947 he became the health minister for the People’s Liberation Army’s provisional government. He continued in this role until 1949 when the People’s Republic of China was established. Only then did he rest. He returned to the land of his birth, Austria. 1952 found him in Israel when he was struck down by an infection. Virtually unknown in the new Jewish State, he was buried in a simple grave and quickly forgotten.

But, China does not forget its friends. Sino-Israel diplomatic ties were reestablished in 1992. Since then, Chinese diplomats stationed in Israel have brought flowers to his grave every year to pay their respects. Last year, The Times of Israel reported that Chinese Ambassador Zhan Yongxin said, "...we want to reaffirm that the Chinese government and its people will never forget the friends who contributed to the founding and development of the People’s Republic.”

The Shanghai Jewish Refugee Museum honored Dr. Jacob Rosenfeld’s memory in 2019 with an exhibit that traced his experiences in China, as well as two other Jewish doctors. The museum itself is a symbol of the life-saving sanctuary that drew Jewish refugees to Shanghai from Europe during the 1930s and 1940s.

|

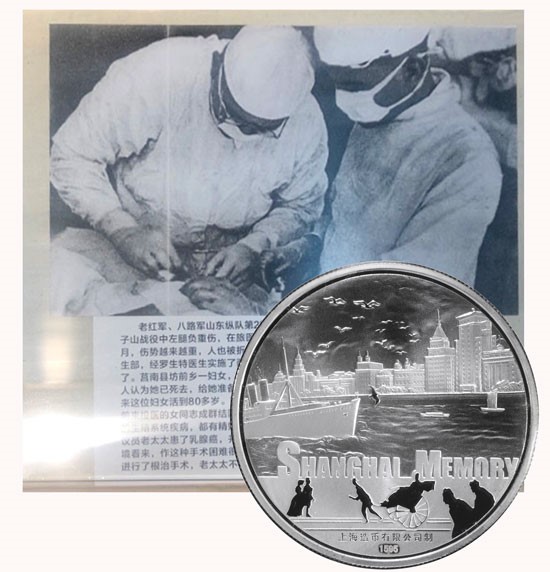

| Dr. Rosenfeld arrived in Shanghai together with thousands of other Jews fleeing from Nazi persecution. He joined the People's Liberation Army as a surgeon and served China until 1949. Shown is the 2013 1 oz. silver Shanghai Memories medal struck at the Shanghai Mint. Behind it is a photo of Dr. Rosenfeld operating in a combat zone.

|

In 2013, a group of gold and silver medals struck at the Shanghai Mint memorialized this experience between China and the desperate refugees who landed on its shores. All the medals were designed by the well-known Panda coin artist Zhao Qiang. There is a 5 oz. gold medal with 36 minted, a 1 oz. gold with 570 struck and a 1 oz. silver medal with 5,773 minted. Each comes with a special box that includes a printed scroll.

It was indeed a good road in China and it changed everyone who followed it, even for a short distance. Dr. Norman Bethune fell along the way. Nurse Jane Ewen returned to Canada in 1939. She did not return to China again until 1986, a year before her death. In her will, though, she asked that her ashes be buried in China. Her daughter observed, “She left her heart there, so it seemed fair that she remains there.”

This story is dedicated to the doctors, nurses and medical staff in Wuhan who gave their lives to fight the COVID-19 virus.

1 Letter to Frances Penney Bethune, September 14, 1937

2 “A Canadian surgeon's red legacy in China,” Xinhua News, December 20, 2019

3 “The Politics of Passion: Norman Bethune's Writing and Art,” by Norman Bethune, University of Toronto Press, 1998

4 “Phoenix: The Life of Norman Bethune,” by Roderick Stewart, Sharon Stewart, McGill-Queen's Press, 2011

5 “The Voyageur Canadian Biographies 5-Book Bundle,” ‘The Scalpel, the Sword,’ Dundurn, 2014

6 “Extraordinary Canadians: Norman Bethune” by Adrienne Clarkson, Penguin Canada, 2009

Peter Anthony is an expert on Chinese modern coins with a particular focus on Panda coins. He is an analyst for the NGC Chinese Modern Coin Price Guide as well as a consultant on Chinese modern coins.

Stay Informed

Want news like this delivered to your inbox once a month? Subscribe to the free NGC eNewsletter today!