NGC Ancients: Coins That Tell the Story of Augustus

Posted on 8/13/2024

The ancient Roman calendar underwent several reforms that shaped the months used by most of the world today. After Julius Caesar’s death in 44 B.C., the month he was born in, Quintilis, was renamed Julius. The month of Sextilis followed suit several decades later when it was renamed Augustus for Emperor Augustus, Julius Caesar’s grand-nephew and heir.

With the calendar once again rolling around to August, let’s take a look at coins that tell the life story of the man the month is named after.

Early life

Augustus was born Gaius Octavius (‘Octavian’) in 63 B.C., the same year this silver denarius was struck by the moneyer L. Furius Cn.f. Brocchus. It shows Ceres with grain on the obverse and a curule seat, a symbol of power, on the reverse. In this same year, Julius Caesar, Gaius Octavius’ great uncle, won an election to serve as praetor.

Julius Caesar’s illustrious political and military career came to an abrupt end on the Ides of March in 44 B.C. when he was fatally stabbed at a meeting of the Senate. Among the senators who conspired to kill him was Brutus, who boldly issued this silver denarius in 42 B.C. showing his own portrait and daggers celebrating his role in Caesar’s murder.

Immediately following Caesar’s murder, the assassins were granted amnesty. But in the ensuing power struggle, Marc Antony managed to drive them out of Rome, and he set himself up as Caesar’s successor. Octavian was still a teenager, but he ambitiously leveraged the power granted to him as Caesar’s primary heir. This gold aureus struck around 43 B.C. shows Octavian on one side and Caesar on the other. Like the Brutus coin, it was struck by a military mint.

The Second Triumvirate

To oppose the allies Brutus and Cassius, Octavian formed the Second Triumvirate in 43 B.C. with fair-weather allies Marc Antony and Lepidus. The three are depicted on this base metal coin struck at Ephesus sometime during the lifespan of the Second Triumvirate, which lasted until 33 B.C.

In late 42 B.C., Octavian and Antony prevailed at the decisive Battle of Philippi, fought in two engagements nearly three weeks apart. By the end, both Brutus and Cassius were dead, two years of civil war were over, and the members of the Second Triumvirate reigned supreme.

Lepidus is often forgotten as the “third wheel” of the Second Triumvirate, for the true power resided with Octavian and Antony. Lepidus and the younger Octavian are shown on this silver denarius struck at a military mint in 43 B.C.

Lepidus’ sphere of influence was Roman territory in Africa, and in 36 B.C., he raised an army that helped defeat the rebellious Sextus Pompey in Sicily. Unfortunately for Lepidus, he subsequently lost a standoff with Octavian over control of Sicily. Deprived of any meaningful influence, Lepidus lived almost another half century as his former ally accumulated unprecedented power.

A military showdown between Octavian and Antony, the two most powerful men in the Roman world, was averted with the Treaty of Brundisium in 40 B.C. It outlined the power for each, with Octavian controlling most Roman territory in western and central Europe and Antony commanding in Greece and Asia Minor.

The two men are shown on this gold aureus struck in the year prior to the treaty. In a further attempt to cement peace in 40 B.C., Antony entered into a disastrous marriage with Octavian’s sister, Octavia.

As for Octavian, his first two marriages were brief and primarily done for political expediency. In 38 B.C., Octavian married his third wife, Livia, who had already been married to another Roman political leader and had two children (one of whom was the future emperor Tiberius), who Augustus adopted. This base metal obol struck in Thessaly between 31 and 27 B.C. shows Octavian and Livia, who was granted enormous power for a woman of her time.

When the Second Triumvirate expired at the end of 33 B.C., Octavian and Antony were on a collision course. Antony's callous divorce of Octavia around this time further aroused public opinion in Rome, which had nervously watched as Antony showered attention and accolades on Cleopatra VII, the Egyptian queen with whom he’d fathered three children.

The final showdown came in 31 B.C., with Antony and Cleopatra’s forces stationed in Greece, and Octavian’s forces moving to confront them at what would be known as the Battle of Actium. After losing the battle, Antony and Cleopatra escaped to Alexandria, Egypt, leaving much of their army behind. After losing the Battle of Alexandria in 30 B.C., both committed suicide.

This Roman silver denarius struck between these decisive battles shows Octavian opposite Victory standing on a globe.

Sole reign

After defeating Antony, Octavian sought to carefully cement his political power and re-establish order in Roman society. In 27 B.C., the Roman Senate gave Octavian the title of Augustus, meaning “sacred” or “revered.” His title appears on this silver denarius struck around 19-18 B.C., possibly in Spain’s Colonia Caesaraugusta, today known as Zaragoza.

In 20 B.C., Augustus secured a major moral victory when the Parthians agreed to return the Roman military standards which had been lost at the humiliating Battle of Carrhae in 53 B.C. This silver denarius shows on its reverse a Parthian kneeling and presenting a standard. The Parthian Empire and its successor, the Sasanian Empire, would fight a grinding series of wars with the Romans for centuries.

Marcus Agrippa was a boyhood friend of Augustus who became a loyal lieutenant, leading his army to victories against the rebel Sextus Pompey in 36 B.C. and against Marc Antony in 31 B.C. Long after these early victories which cemented Augustus’ power, Agrippa was rewarded with substantial political power.

Augustus adopted Agrippa in 17 B.C. to pave the way for his smooth succession as supreme leader, but that option was derailed when Agrippa died in 12 B.C. Agrippa is portrayed on the reverse of this silver denarius of 13 B.C.

Golden years

In 2 B.C., after a long period of peaceful rule, the senate conferred upon Augustus the esteemed title of “pater patriae,” father of the country. It previously had been given only twice: to Marcus Furius Camillus in 386 B.C. (for liberating Rome after it was sacked) and to Cicero (for uncovering a conspiracy in 63 B.C.). The title is seen on the obverse of this silver denarius stuck sometime between 2 B.C. and A.D. 12.

In 4 A.D., Augustus formally adopted his stepson Tiberius, putting him in line for succession. The coin shown here, a silver denarius struck in Lugdunum around A.D. 13-14, shows Augustus on the obverse and Tiberius on the reverse. Not only was Tiberius his adopted son, but he had distinguished himself with military victories against Germanic tribes.

A great setback in Augustus’ life and reign occurred in A.D. 9, when Germanic tribes dealt the Romans a stunning defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Three Roman legions led by Publius Quinctilius Varus were ambushed and destroyed. Augustus was reportedly so despondent that he repeatedly shouted in despair: “Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions!”.

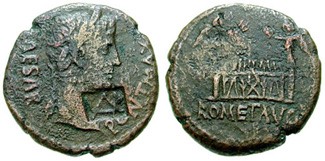

This base metal coin called an “as” was struck at Lugdunum around 15-10 B.C. It shows the head of Augustus opposite a famous altar in the mint city. Importantly, it bears a countermark of Publius Quinctilius Varus, whose earlier governorships in Africa, Syria and Judea, were eclipsed by the magnitude of his incompetence and defeat in Germany.

On August 19, A.D. 14, Emperor Augustus died at age 75. He was promptly proclaimed a god, a status reflected in the word DIVVS on this base metal “as” struck after his death by his adopted son and successor, Tiberius. Though the transition of power from Augustus to Tiberius did not occur without incident, it occurred relatively peacefully – in sharp contrast to many transitions that would occur in subsequent decades. In fact, of the “Twelve Caesars” (which include Julius Caesar and the first 11 emperors), only about a third died of natural causes, while the rest were murdered or committed suicide.

Images courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group and Heritage Auctions.

Related Link: More NGC Ancients columns

Stay Informed

Want news like this delivered to your inbox once a month? Subscribe to the free NGC eNewsletter today!